With its deadline only a few days away, there seems a high probability that the deficit supercommittee will fail to reach consensus. Then, there may be cuts in defense spending that many, including Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, deem disastrous.

Such spending accounts for about 19 percent of the federal budget for fiscal year 2011 and 5 percent of total national output. And as usual, the nation is divided on the importance of such spending. This largely follows the pattern of the political left favoring cuts and the right opposing them. However, isolationist currents also are flowing, with many conservatives, typified by Rep. Ron Paul, R-Texas, advocating that the country withdraw from overseas operations and commitments.

So the situation is interesting, to say the least. To understand it, a review of how such spending has evolved is useful as is an examination of features of military outlays not shared by most federal programs.

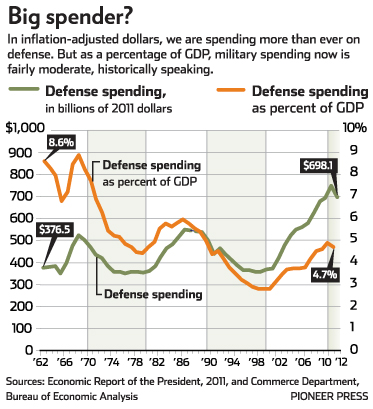

Look first at trends. At some $750 billion, inflation-adjusted spending in fiscal 2011 for military programs of the Department of Defense is at its highest in the past 50 years.

It is more than twice as much as in any fiscal year from 1996 through 2001 and is up $70 billion, or 11 percent, from FY 2009, the last Bush administration budget.

It remains, however, well below the $1 trillion outlays of 1944 and 1945, when the U.S. economy was only one-sixth as large as it is now.

In that context, “automatic” cuts of some $500 billion over the next 10 years may not seem like much, even when added to the $450 billion already planned.

Note that these cuts are from projected levels of outlays that would take place if force levels stayed near current and all scheduled hardware purchases went ahead. Such “cuts” are not the same as actual reductions from this year’s spending levels.

Taken relative to the economy, however, current military spending was higher in half of the preceding 50 years. At 4.9 percent of gross domestic product, it is lower than in any year from 1941 through 1975 and is exactly equal to the last fiscal year of the Carter administration. And, compared with late World War II, when this proportion exceeded 36 percent, current military spending is low indeed.

Finally, although defense’s share of total federal spending – now at 19.4 percent – is a bit higher than in the 1990s, it remains lower than in any year from 1941 through 1992.

So there are arguments for both sides. In relative terms, defense spending was greater in the past. But in absolute terms, it is much higher than the 1990s.

Many people will ask why, if we are leaving Iraq and will reduce forces in Afghanistan soon, we could not cut spending to 2007 levels, when conflict in Iraq was at its peak. That would reduce outlays by $150 billion a year, some three times as much as the cuts that would come from a failure of the supercommittee. Are Panetta and other defense advocates crying wolf?

There are complications, particularly from the fact that government accounting differs from that of the private sector.

When a business buys a new machine, its balance sheet shows one asset, cash, being traded for another asset, the machine. But the business will depreciate the cost of that asset over many years, allocating the expense over its useful life.

The government does not maintain a balance sheet. When it buys a new airplane or ammunition, it appears as an expense in the year the outlay is made, even if the ammunition is not used until much later and the airplane flies for decades.

We spent enormous amounts on defense in 1942-1945. Some of that was for things – fuel, rations, ammunition – that were used immediately. But it also went for ships the Navy used for decades and bombs used in the Vietnam War.

In 1969, when I first set foot on an aircraft carrier, it was the same USS Essex my uncle flew a torpedo-bomber off of in 1945.The B-52s still in use are older than nearly any of the pilots flying them.

If the government used accrual accounting like everyone else, the tabulated defense expenditures of the 1940s, 1960s and 1980s, when we bought a lot of hardware, would be lower but those of other years higher.

Defense outlays from 2003-2009 understated the true cost of defense because we were using up stocks of ammunition and other expendables and wearing out tanks, Humvees and other Army and Marine Corps machinery much faster than we were replacing them. Even ships and planes not heavily engaged in the war aged.

We are catching up by rebuilding war stocks. The danger of not doing so was evident this summer.

France and Britain were hot to use military force against the Libyan dictator Gadhafi but embarrassed themselves by running out of bombs in a few weeks and had to come to us for more.

Similarly, we are only now bringing Army and Marine equipment back to what it was a decade ago. The Navy and Air Force have much hardware purchased during the Reagan administration’s procurement bonanza. That was 30 years ago, however, and it is wearing out.

Where you come down on all of this depends on how you weigh risks and opportunity costs. I would be willing to maintain current levels of military spending if the government were willing to raise taxes back to the levels that prevailed in the 1980s and 1990s.

That would return revenue to at least 18 percent of GDP, up from the 14.5 percent we have this year, and would raise another $525 billion per year. But many people apparently cannot countenance that.

© 2011 Edward Lotterman

Chanarambie Consulting, Inc.