People think presidents have a lot of power over the nation’s debt versus its economic growth. They should be looking at Congress.

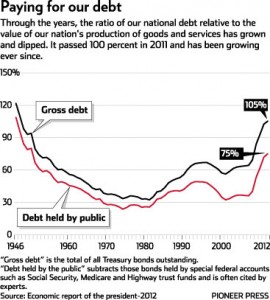

The U.S. national debt, compared with total national output of goods and services, or gross domestic product, fell almost continually from 1946 to 1981. Then this ratio rose for 15 years, doubling by 1996 from 1981 figures. Then there was a five-year decline. Since 2001, the ratio has risen continually and will continue to rise unless large changes are made in taxes and spending.

Should we conclude that the presidents during that initial period — Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford and Carter — all made this measure of the debt fall? Were Reagan and George H.W. Bush responsible for its rapid rise, with the absolute value of the gross debt more than quadrupling during their 12 years in the White House? Did Bill Clinton’s stewardship cause the five-year fall? And should we fault George W. Bush and Barack Obama for the increases since then?

Should we conclude that the presidents during that initial period — Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford and Carter — all made this measure of the debt fall? Were Reagan and George H.W. Bush responsible for its rapid rise, with the absolute value of the gross debt more than quadrupling during their 12 years in the White House? Did Bill Clinton’s stewardship cause the five-year fall? And should we fault George W. Bush and Barack Obama for the increases since then?

The basic answer is no. Strictly speaking, presidents have no control per se over taxes or spending, though they may exercise much influence in the process. Presidents can send proposed budgets to Congress and can veto tax and spending bills passed by Congress. Beyond that, they have no constitutional power over fiscal affairs. On their own they cannot choose to spend money or alter taxes.

Yet many in the general public apparently believe that presidents have such powers and that, if the national debt is increasing by a trillion dollars per year while Obama is in the White House, it is his doing. The same thinking holds that if the national debt nearly tripled during the years Ronald Reagan was in office, he was responsible.

This is the sort of “post-hoc logical fallacy” that would earn an F in any freshman econ or philosophy course, but it dominates public discourse, in part because elected officials are quick to grab credit when something good happens. Unfortunately, this generalized misunderstanding that presidents control spending blights rational discussion of the problems we face.

This reflects a failure in the teaching of what we called “civics” when I was in the seventh grade and perhaps “American government” now. In our Constitution, Article 1, Sections 7-9, the responsibility of Congress for taxing, spending and borrowing is laid out in detail, including the provisions that “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives” and that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”

In contrast, the Constitution gives no specific rights or powers over taxing, spending and borrowing to the president, other than his role of signing or vetoing bills passed by Congress. Subsequent legislation in the 20th century requires the president to submit a budget proposal to Congress, but this is not required by the Constitution.

Now, it would be highly disingenuous to leave it at that. Especially over the past 80 years, presidents have played an active role in fiscal affairs. The president’s prerogative to veto has always conferred great bargaining power.

Ronald Reagan had no control, but he asked Congress for the tax cuts and spending increases that made the debt balloon.

And Congress, where Democrats had a solid majority in the House for all of Reagan’s eight years, largely gave him what he asked for. Significant numbers of Democrats in both houses voted for the tax cuts and the spending increases.

Bill Clinton had no control, but he did ask for a tax increase that a Democratic-controlled congress granted, although all Republicans voted no.

He asked for real cuts in defense spending that were passed by congressional Democratic majorities before 1995 and by Republican ones after that. He objected to small trims to social programs passed by a Republican majority in his last six years as president, but did not veto any appropriations bills.

Similarly, George W. Bush had no actual control over taxes or spending.

But he did ask for two tax cuts, for a Medicare drug benefit and for approval of going to war in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Again, Congress largely gave him what he wanted, with some Democrats voting for each of these measures that, taken together, made the national debt grow sharply. Congress had the power and could have chosen not to approve Bush’s requests.

Remember that the Bush tax cuts were passed as “temporary” ones that would cancel out after 10 years.

This was because it was clear that the deficit would begin to balloon as time went on. In 2007, before the financial crisis unfolded, the Congressional Budget Office was projecting a budget deficit exceeding $1 trillion for 2012.

So what about Obama? He asked for and Congress approved the second half of the $700 billion TARP package originally sought by the Bush administration, although most of that money was never spent. He asked a Democratic-majority Congress for and got a $789 billion stimulus package that was 65 percent extra spending and 35 percent tax cuts.

He sought and received approval of the controversial cash-for-clunkers and auto bailout programs. He asked for and got the two-year temporary reduction in FICA taxes that has just expired.

He asked for and got health care legislation that has had little effect on spending yet, but that will greatly increase Medicaid outlays starting in 2014.

He enjoyed Democratic control of Congress during his first two years in office. So he and congressional Democrats must share responsibility for the deficits in fiscal years, even if the tax increases and spending cuts that would have been required to erase them would have been disastrous policy in that economic situation.

It is also clear that he would have liked to spend even more if it had been possible to get it through Congress.

But what about the years since 2010, when a Tea Party-bolstered Republican party retook control of the House and reduced the Democratic majority in the Senate to 51 plus two hangers-on?

This period represents perhaps the worst breakdown ever of our constitutional system of divided branches of government.

Blame can be assigned to all parties involved. But the economic and political dynamics of this debacle must be left to a future column.