Beef prices are rising so sharply that it’s possible McDonalds will be forced to remove its popular McDouble from the Dollar Menu. The item’s high beef content makes the ratio of ingredient cost vs. price less favorable than for other menu items.

Now, that’s a national crisis.

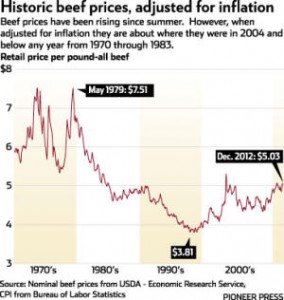

Less facetiously, USDA’s weighted average of all retail beef prices hit a new high of $5.12 per pound in December, up about 3.5 percent since August. Indications are that they have continued to rise since then. However, adjusted for general inflation, they remain in a band that has prevailed for 30 years and are still below any time from 1970 through 1983.

It also is an opportunity for economics teachers because the story of the beef price spike is chock-full of examples of economic principles at work.

Start with the simple principle that supply — a producer’s willingness to sell different quantities of a product at different prices — depends on the marginal cost of production. Marginal cost is the increase in total cost from producing one more unit of the product.

News stories correctly note that beef is going up for two related reasons. A multiyear drought has been the scourge of some areas like Texas, which have many cow-calf operations, meaning many ranchers began to liquidate at least parts of their herds in the past year. Moreover, in the shorter term, the more widespread lack of rain over corn-soybean growing regions in 2012 has pushed up feed costs for cattle feeders.

News stories correctly note that beef is going up for two related reasons. A multiyear drought has been the scourge of some areas like Texas, which have many cow-calf operations, meaning many ranchers began to liquidate at least parts of their herds in the past year. Moreover, in the shorter term, the more widespread lack of rain over corn-soybean growing regions in 2012 has pushed up feed costs for cattle feeders.

As I noted in a July 22 column, the short-term response to forced herd liquidations such as this is a decline in meat prices because the sale of breeding animals increases the supply. But after that immediate effect, prices start to rise because fewer young cattle are on the way to feedlots, thus driving up costs.

That could happen at any time. In fact, it was already happening because the drought in ranching areas occurred before the drought in corn-growing states.

So feedlots now face higher marginal costs, not only in the purchase of feeder cattle, but also in the feed needed to fatten them. As an introductory micro-econ class explains, they will keep on producing the same quantity as before only if the price rises.

Note that cattle feeders cannot choose to raise their selling price.

Although the sector is much more concentrated than a few decades ago, it still is competitive enough that most feedlots are “price takers.” They can either accept market prices or choose to not produce. But if enough of them do choose to cut back on production, then prices rise — at least after a short delay. That is why price increases are more perceptible now, even though the drought is months in the past.

Something more complicated also goes on that involves different categories of costs. Ranching involves a lot of fixed assets such as land, fences and watering equipment, plus the breeding herd itself. These have to be paid for as long as a rancher is in business and are largely independent of output. Thus these costs are fixed, unlike those for crop inputs such as diesel fuel and fertilizer.

As long as the price received for one more feeder calf is equal to the increase in costs related to raising that additional calf, a rancher should keep producing. This can be true even if the average amount received per calf is less than the average cost of producing one, considering both fixed and variable costs.

As long as a cattle ranch can pay the variable costs and some of the fixed costs, it can keep on going. It is now in a “loss minimizing” mode rather than a “profit maximizing” one, but that is a familiar situation for many in agriculture and small business.

The next step in any standard econ text is to note that once the price drops so much than you cannot cover even variable costs, you should cease production.

With so many fixed costs and so few variable ones, ranchers don’t hit that point often. They have good years and bad ones, but they keep raising cattle. But the cost of trucking in feed to maintain a herd all through a year can be so high that they call it quits.

In the real world, many ranchers may keep on producing even if the sale price does not cover all variable costs as long as they expect the situation to be temporary. Losses eat up net worth, but their families have decades of experience raising cattle and know droughts eventually end. Liquidating the operation is a last resort.

But even operators that continue in business cull the least productive stock. That was happening months ago and was a much bigger factor in the temporary increase in meat supply and the decrease in calf production than was the liquidation of ranching businesses.

In contrast to ranching, cattle feeding involves many more variable costs and fewer fixed costs. Moreover, while not all do so, feedlot operators are fortunate in that they can use futures markets to lock in prices for three major variables ahead of time: what they pay for feeders, what they pay for feed and the price they will get for the fat cattle they sell.

If these prices are such that they cannot lock in a profit over variable costs, they can let the lot stand empty for a while.

The upshot is that while both are “in the cattle business,” the two halves of the production cycle vary greatly in the degree of risk and variability of income.

Many people are aware that cattle and hog prices follow a cyclical pattern for the same reasons there are cycles in ocean shipping rates, office space rental rates and salaries of aeronautical engineers. (See April 1 column for details.)

So ranchers are familiar with price variation. Against that backdrop, the drought is an “exogenous shock” that is affecting the system.

If it affects only one sector, like beef production, an exogenous shock is no big deal. But some have altered history.

As Keynesian economic theory waned in the 1980s, a group of economists who were critical of Keynes argued that instead of fiddling with how government might respond to periodic economic fluctuations, it was more important to understand the fundamental reasons such cycles develop.

These “real business cycle” theorists, including Edward Prescott, 2004 Nobel laureate and longtime University of Minnesota professor, found that exogenous shocks — including political events such as wars or oil embargoes and technological innovations like steam engines, electric motors and integrated circuits — were an important cause of booms and busts.

For most consumers, higher beef prices are unwelcome. Nonetheless, the beef market demonstrates how economic forces play out in the real world.