The national jobs situation continues to improve slightly. At its August level of 7.3 percent, the unemployment rate is back to where it was at the close of 2008 and down by a fourth from its November 2009 peak. At 144.2 million, the number of jobs is up some 6 million from its low and getting closer to its previous peak of 146.7 million. So things could be worse

The problem is that this previous high had also been hit nearly six years ago, in November 2007. Since then the U.S. population has increased by 13 million. The number of people over age 16 and not in the armed forces, prisons, mental hospitals or other institutions is also up 13 million. But the labor force, which is all the civilian, adult, non-institutionalized people who have jobs or are actively seeking them, is up only 1.7 million.

Yet we remain with 2 million fewer jobs than then. Taken from that perspective, without considering other nuances, the jobs situation remains disastrous. To reach the same number of jobs relative to population that we had six years ago, we would need an additional 11 million employed, not the 2 million that would bring us up to the same absolute high point.

So how can the unemployment rate be dropping? The answer is that the unemployment rate is not calculated as unemployed people as a percentage of the population, but rather as a percentage of the “labor force.” That is: people with jobs plus those actively seeking them. If you don’t have a job and are not taking specific actions to secure one, you are not “unemployed;” you are “out of the labor force.”

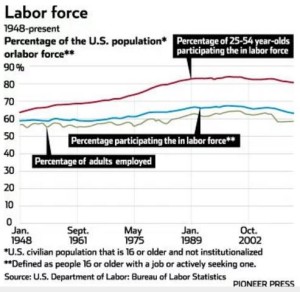

The unemployment rate has been dropping in part because while the number of people with jobs has been inching up, people also have been dropping out of the labor force. The size of the labor force compared with the eligible population (older than 16, civilian, non-institutionalized) is called the “labor force participation rate.” For that rate to be as high now as it was at the dawn of the century, some 10 million people would have to rejoin the labor market.

Combine that with the number of jobs we actually had this past August, and we would have an unemployment rate of 13 percent, not 7.3 percent. So, much of any improvement in what economists call the “headline” unemployment rate is due to people dropping out of the labor pool, rather than from new jobs.

Pretty dismal, huh? People on the political right are quick to blame the president for opposing job growth policies. Those on the left level the same charges at Congress. Both ignore the complexity of the situation, ones that will bedevil whoever controls the levers of power in Washington for years to come.

Looking at the long-run pattern of these rates and we see a different picture. The LFPR and the ratio of jobs to population have been trending down for at least 15 years now, starting well before the financial crisis. But they had been rising for 40 years prior to that. The averages for the months Barack Obama has been in office are the same as those for the equivalent months of Ronald Reagan’s administration. Considering that the fraction of the population over age 65 has risen substantially in the past 30 years, we are not necessarily doing badly.

Looking at the long-run pattern of these rates and we see a different picture. The LFPR and the ratio of jobs to population have been trending down for at least 15 years now, starting well before the financial crisis. But they had been rising for 40 years prior to that. The averages for the months Barack Obama has been in office are the same as those for the equivalent months of Ronald Reagan’s administration. Considering that the fraction of the population over age 65 has risen substantially in the past 30 years, we are not necessarily doing badly.

That introduces a crucial and oft-ignored factor, the age structure of the population.

There was a long, slow run-up in labor force participation that began in the early 1960s and continued for 35 years. If you consider only people of prime working age, 25 through 54, the uptrend began even earlier. There are at least two reasons for these increases.

Some of the general increase was due to the baby boomers starting to hit the labor force by the early 1960s. There had been a “birth dearth” during the Depression and World War II, so when the first boomers began graduating from high school in 1964, it was the beginning of a surge of young people into the workforce that dramatically changed the proportion of adults actually of working age.

The most common reason adults are not in the work force is that they are retired. But as 81 million boomers became adults (by Labor Department definition of age 16 and over) between 1962 and 1980, the number of retirees relative to workers had to fall and it did. So the LFPR rose.

This was compounded by social changes such as decreases in family size and the ethos that women should have careers outside of the home. More women went to college, and now a higher proportion complete college than men. With smaller families and more day care options, even women who had children began to spend nearly all their adult lives in the work force.

These long-term factors were powerful. But the baby boom ended in 1964. And the increase in women’s labor force participation had to taper off as nearly every woman of working age who wanted a job got one. So the trend could not go on forever.

Indeed, as boomers reached retirement age, the ratio of people over 65 relative to those of prime working age was destined to rise. The first boomers qualified for early Social Security in 2008 and now there is a torrent, with thousands reaching full retirement age every day. The last ones won’t do so until 2031, when those born in 1964 turn 67. In the interim, we will have many more people of retirement age relative to those of working age than we ever had before. That is part of the problems of Social Security and Medicare. It will drive changes in labor force participation rates and the percentage of the total population that has jobs. We have known for a long time that both were destined to fall. The only question is how much.

All this is not to say that the aftereffects of the financial crisis are not an important factor. They certainly are. Participation rates have fallen for those ages 25-64 and that drop cannot be due to baby boom retirements. If one looks only at men, the rate of fall is even faster. While the rate for both sexes is still 15 percentage points above levels 60 years ago, that for men is hitting historic lows. These are other societal changes that are adverse, but too complex to address here.

The important thing is to remember that multiple factors are at work in labor markets right now and not try to use short-term policies to address long-term problems. That usually makes things worse rather than better.