Copper-nickel mining in northeastern Minnesota remains in the news as PolyMet’s environmental impact statement was deemed adequate by the state last week, putting the project one step further on a long path, with many needed permits yet ahead.

But Twin Metals’ proposed underground mine near Birch Lake was set back as Gov. Mark Dayton refused to give access to state lands for exploratory work and the federal Department of the Interior warned that renewal of two key leases on federal land won’t be automatic.

It is impossible to say how these two mining initiatives will turn out.

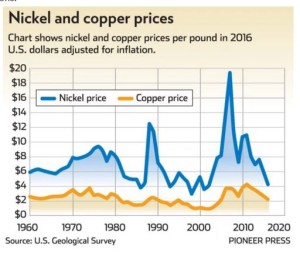

There is some irony that acceptance of PolyMet’s EIS came through just as copper and nickel prices continue to fall sharply. The project has been in the works for years, first announced as the global commodity boom emerged a decade ago. But since 2011, the trend in prices has been downward. The price of nickel dropped 60 percent over the past five years and that of copper by nearly half. Moreover, prospects for the global economy are such that the slide may continue for some time. A return to even the average price of the last decade may not come for many years. Of course, the projects, if they ever get off the ground, can be expected to be around for many years.

So what does this mean for these two projects in the news and for U.S. metal mining in general?

The key, as in all business decision-making, is balancing of revenues and costs or, in different terms, of income and expense. That is easier with a short-term business, say, opening a specialty kiosk in a mall for the 10 weeks prior to Christmas. It is hard when planning a venture such as mining that will last for 20 years or more.

Let’s start by thinking about costs. Intro econ students learn the important distinction between fixed costs, variable costs, sunk costs and marginal costs. The first do not vary with the level of output and must be paid even when output is zero, at least as long as the business does not go bankrupt. Variable costs do go up and down as output changes, and when output is zero, so are these costs.

Modern metal mining is an industry in which fixed costs are huge — both in absolute terms and as a portion of the total cost of production over the life of a project. Just getting to the point where ore can be extracted can take years and tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. For open-pit operations like PolyMet’s proposal, much of this is to remove the overburden, the valueless soil and rock that lie atop the valuable ore. This can amount to millions of tons that must be excavated and moved.

For an underground operation, shafts must be sunk, lifting, ventilating, dewatering and compressed air machinery installed. For both types, some ore-processing plant must be built.

Once all this is in place, mining can begin and variable costs incurred. These include the fuel and electricity, labor, repairs and maintenance and supplies like explosives that are used to actually produce ore rather than preparing the project up to this start point. Revenue from sales of metals or ore must not only pay these operating expenses, but there must be enough additional to amortize the up-front investment over the life of the mine.

Once the mine is developed, the costs to that point are largely “sunk” from the point of view of society as a while. That is, the labor, fuel, machinery use, explosives and so forth are gone forever. Moreover, the mine will be there whether worked continuously or not. So from then on, the question of whether or not to work the mine depends on the added or “marginal” revenue from selling output versus the added, or marginal, costs of operation.

As long as the extra revenue from operating exceeds the extra cost, whoever owns the mine will run it. They also would like sufficient surplus to pay off all of the fixed investment, but that doesn’t factor into the decision of operating.

The fixed costs of getting a particular mine to the point of operation can be estimated accurately. Revenues and operating costs over the life of the mine are more difficult.

Revenue depends on price of output. Prices of natural resource commodities tend to fluctuate sharply over time. Adjusted for inflation, the long-term trend in such commodity prices is downward. (This is less true for metals and ores than for grains and oilseeds.)

One could look at trend lines and assume that what has happened over the past 20 or 40 years will continue. However, the fluctuations are hard enough that any mine in operation for a specific 20-year stretch may face average revenues well above or well below longer-term trends. Someone looking at the preceding 40 years when contemplating opening a mine in 1995 would have missed the greatest boom in generations.160313NickelAndCopper-WEB

One could look at trend lines and assume that what has happened over the past 20 or 40 years will continue. However, the fluctuations are hard enough that any mine in operation for a specific 20-year stretch may face average revenues well above or well below longer-term trends. Someone looking at the preceding 40 years when contemplating opening a mine in 1995 would have missed the greatest boom in generations.160313NickelAndCopper-WEB

Gencore, the multinational that owns PolyMet, knew back in 2006 that the developing boom would not last forever. And it knows the current bust won’t, either. But exactly what the average will turn out to be is not only unknown but unknowable.

That is because events like the dramatic growth of the Chinese economy over the past four decades are an example of what economists term “uncertainty,” when there is no statistical or actuarial basis on which to compute specific expectations. One can examine a range of alternate scenarios, but the final decision is subjective.

Future commodity prices are not the only uncertainty. Future operating costs may vary, too. Hardly anyone anticipated the jump in diesel fuel costs that took place after 1973 or the present decline in natural gas costs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics computes a specific producer price index for “Copper, Nickel, Lead and Zinc Mining.” That, too, shows considerable variation over the past 30 years. And in the past five years, it has fallen by the same degree, as have prices of copper and nickel. But this is not likely to fall further, while metals prices well may.

Mining firms make sophisticated analyses, but irrationality enters in. Over the decade starting in 1998, during which Chinese demand drove commodity prices upward, many existing mines increased output capacity and new ones were opened. Everyone knew the boom was unsustainable, but there was the temptation that one’s own particular project would pay off before the bust came.

That capacity increase is now a sunk cost. Global output won’t quickly revert to what it was 20 years ago. Even if firms that increased capacity go belly-up as a result, someone will buy the mines at a reduced price and continue operating.

Will PolyMet really bite the bullet and go forward? Gencore says it will. The financial cost of continuing with the permitting process is low compared with the investment that will be required to actually open the mine. But prospects for the metals sector are much less positive than when the process started, and the outcome is not certain.